The Monstrous Sublime: Finding Character in Chaos

My favorite thing is monsters. I have written previously about how the hybridity of the mythical chimeric monster mirrors the transgressive, transdisciplinary splicing of art and science in works of BioArt. In that article, I describe how researchers theorize that the longevity and global prevalence of the chimeric monster myth may be explained by the “cognitive stickiness” of their folk taxonomic “category violations.” That is, men are not fish and fish are not men, thus the mermaid captivates us. The same explanation may account for the popularity and novelty of “genre-bending” music, film, art, literature. Every novel innovation is a synthesis of previous ideas. This is biblical; as King Solomon said, “There is nothing new under the sun;” all that we can conceive is derivative, or, differently, ideas are cyclical—constantly thought, forgotten, rediscovered, suppressed or discarded. And so with the Bible itself, the Flood and Noah’s Ark mirror the Babylonian story of Utnapishtim, Genesis resembles the creation story of the Egyptian cosmology, and attitudes towards the liminal, wise, trickster snake inherit from many legends of the time. The idea that humans across cultures independently arrive at universal, shared belief is well-worn, studied endlessly by anthropology, folk studies, and psychoanalysis, and it need not be rehearsed here. This time, instead, I am inspired to discuss why I love monsters, why I think creating a monster is the ultimate creative act, why I think God loves monsters, and why I think you should love monsters too.

Briefly, to understand monsters is to recognize a fundamental formula: Monster = Creature + Myth. A creature alone is inert, awaiting animation by myth. Myth spawns an egregore of belief around the creature, transfiguring it to a memetic monster in our collective consciousness. Myth makes the monster real. Now, a triptych of mini-essays on three of my own monsters and, in turn, myself:

Caging the Monster

“The monster of prohibition polices the borders of the possible.”

—Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Monster Culture (Seven Theses)

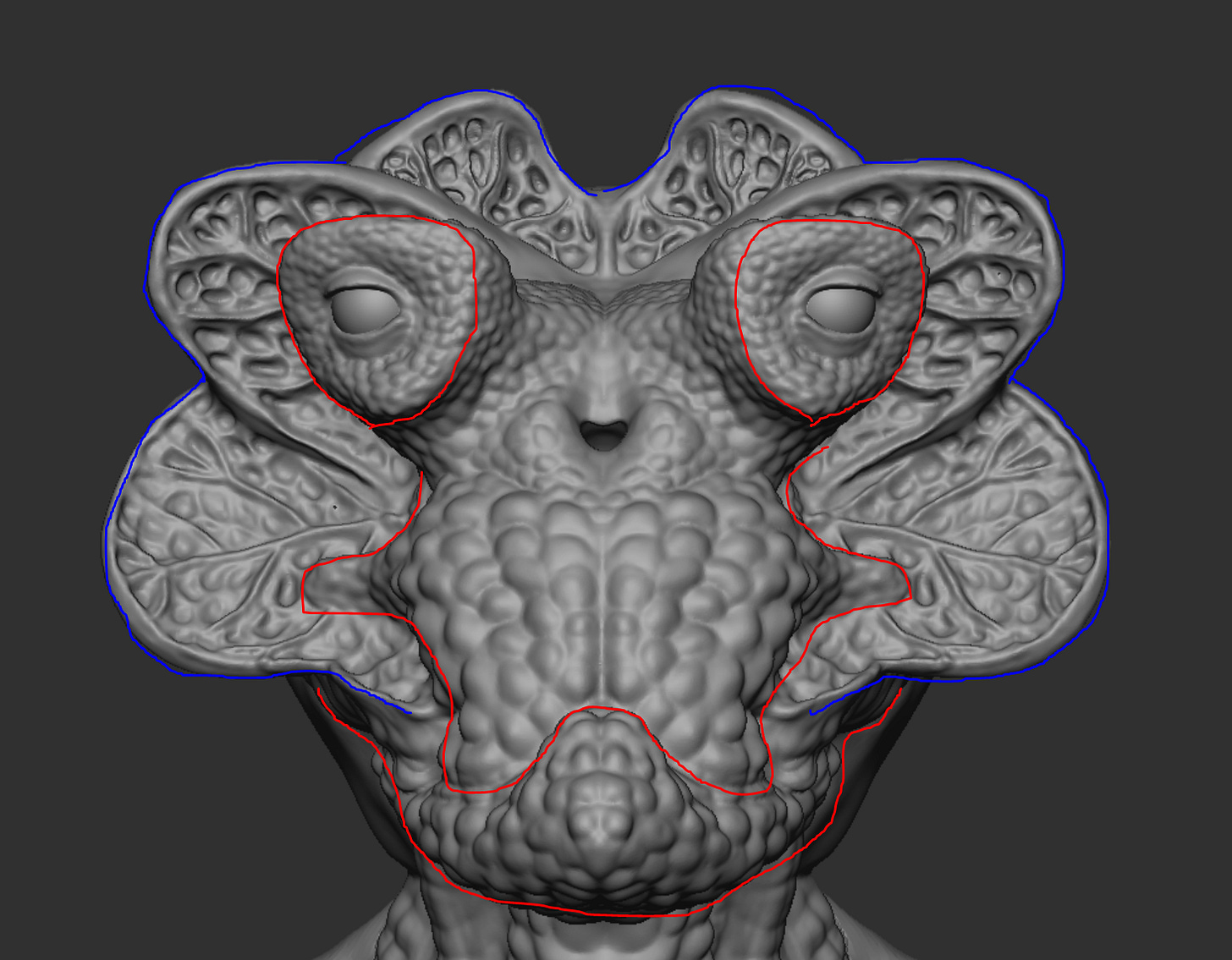

In continuing with the chimeric model, I present Dogsnail, a creature I first sculpted in 2019 but never finished, which conflates forms of man, dog, snail, and…cabbage, roughly. I often approach creature design as study, abandoning it the moment it feels resolved. This is the case with Dogsnail, who I had originally imagined as a sympathetic monster character for a film about a real monster that is mistakenly cast in a schlocky horror B-movie by a sleazy film director who self-identifies with his creatures—think tragicomic exploitation, Universal Studios era monsters, masks and identity, monster and maiden.

Monsters in film are…complex, and, in my opinion, taken for granted and commodified. Much wisdom exists on how to design creatures for film technically, and it mostly resembles design advice for any other work: find a strong silhouette; use natural references; approach forms in a primary, secondary, and tertiary hierarchy. But the monster that haunts every creature designer is this: how do you make a creature memorable? I once naively asked this question of Jared Krichevsky (Godzilla, Transformers, Guardians of the Galaxy), and he replied with an anecdote: a studio exec—some man in a suit—once said, ‘This creature looks great! Can you make it more memorable?’ Sometimes, the only monster behind the mask is capital. William Brown and David H. Fleming note how the cephalopod has become Hollywood’s default monster in their book The Squid Cinema From Hell: Kinoteuthis Infernalis and the Emergence of Chthulumedia. They use the cephalopod’s omnipresence in digital media to slipperily advance the tentacular squid as both a symbol of and an alternative to capital. More invisible tentacle than invisible hand. Even without engaging with Brown and Fleming’s entangling thesis, the squid is clearly an aesthetically convenient choice for studios seeking to signal otherness without investing in originality.

But capital is not the only force to try and cage the monster. Horror purists often complain that film monsters lean too bipedal, too humanoid. In Dogsnail’s defense, his narrative demands he be mistaken for a man in a suit. And anyway, I’d cite the great Leonardo da Vinci here—who insisted that to be a great artist, one must master both man and beast. Or something to that effect—I couldn’t find the exact quote, but he did say, “Man has been called the world in miniature,” and “Animals are the image of the world,” so true by congruence, I would argue. Below are the forms, man and mollusk, I am fond of in this work… Every creature is a design-engineering challenge: from how to suggest human analogs, like the snail-esque cheek protuberances nodding at the human zygomatic arch, to how to subtly connect his cabbage-patch Dilophosaurus crest between the cranium and the jaw; how to achieve a dog-like jowliness with a real sense of weight; and these beautiful, rounded, upside-down trapezoidal eyestalk ends that feel compressed, like a pushed-in pig nose or stumpy bulldog snout. I echoed the unnatural trapezoidal forms in his sagging chest and the crest in his ridged, exoskeletal, mycelial pelvis later.

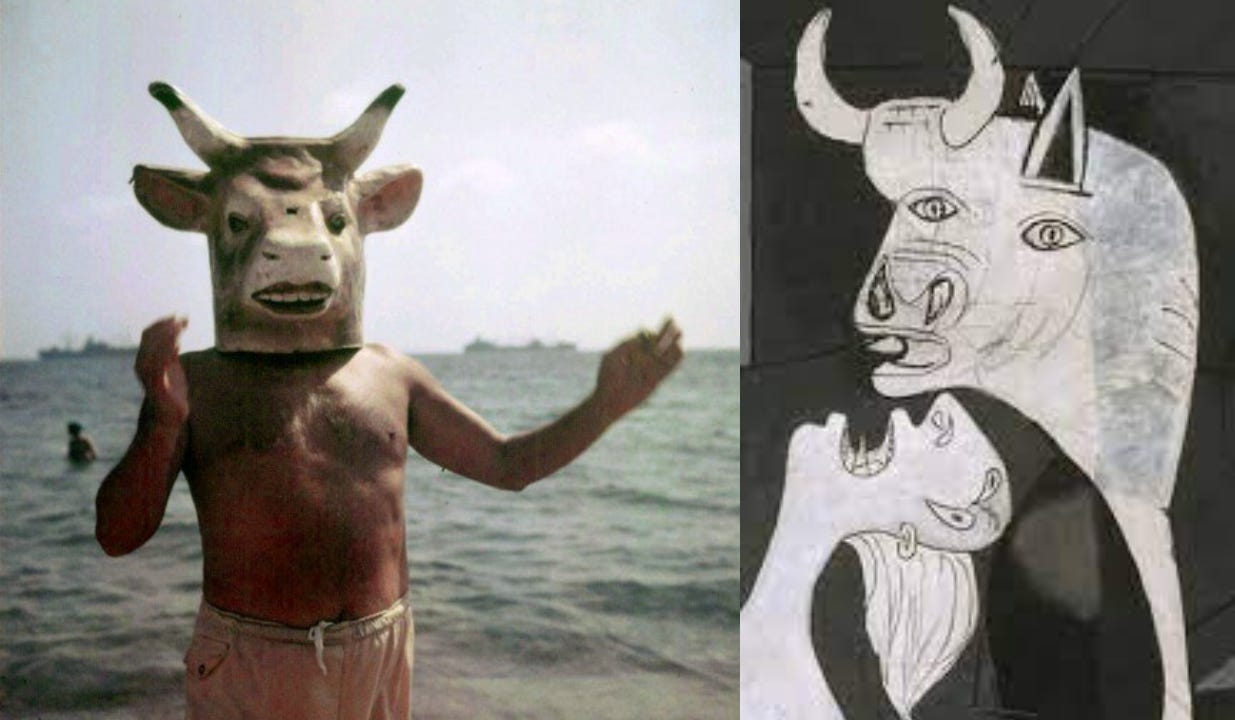

And then, my inspiration for Dogsnail: The mind is strange—as we saw with the categorical mismatching of folk taxonomy—and it could very well be the name "Dogg" that's created this connection in my brain, but I have a strong association between Snoop Dogg and a languid, lanky, laid-back personality that I wanted to capture in Dogsnail. Snoop occupies the same backroom of my subconscious as the cartoon dog Droopy with his droop and drawl and sideways glances. Even his locs read to me like basset hound ears. That is the essence of monstrosity. Synthesis. Semiotics. Syncretism. Inspiration comes from everywhere.

I also wanted to invoke the structure of cabbage, particularly that vascular, chlorophyllic venation. Snail and cabbage, it makes sense. Guillermo del Toro, who understands creatures, has said "Imagine designing a fish and not providing it with a proper aquarium […] Such is the delicate task of designing a monster and its environment. It is a multi-layered task and one that uses image as a storytelling device. Like a piece of art […] a glance at the monster tells you its story and purpose and what it represents." He gets it. We find the Faun of Pan’s Labyrinth camouflaged as part of his environment, runed to match the ones on his skin. Creature is environment is creature. Perhaps Dogsnail is the result of a toxic waste dump gone wrong, fusing discarded cabbage with snail and dog, or maybe he hails from a planet of vegetarian Rasta ganja farmers, here to spread peace and love. The point is the design is storytelling. It suggests a rich inner life, a soul.

When we encounter something we don’t understand, our minds are quick to categorize (or cage) it using any reference we can. A common experience I’ve had when showing my creatures to family and friends is to hear, “It looks familiar…” or to watch as they try and place where they’ve seen it before. With Dogsnail, for example, I often get, “It looks like that thing from Stranger Things” (the Demogorgon) no doubt because of the petaled silhouette, a venus fly trap where face should be. Honestly, it can be artistically demoralizing: to try and create something wholly new—alien, but grounded in reality—only to be told it’s been done before. In moments like this, it is important to remember: this is just the psychology of the human brain at work. When our notion of what is possible is challenged, we cling to our internal library of experience to domesticate the idea and protect our worldview. Horror movies are fun because we know they are fake. To truly encounter the ineffable would destroy us!

The impulse to categorize extends beyond monsters—it's a protective social mechanism that leads us to cage each other daily, reducing complex inner lives to surface impressions based on presuppositions. Or, we might cage ourselves, conforming to the expected roles and behaviors projected on us by others. Which brings me to another baffling cultural bias: the idea that artists who create monsters must be demented, disturbed, or simply weird. I’d like to believe that this bias persist from the romantic myth of the mad artistic genius, but the attitude today is not as flattering. I’ve often been asked why I don’t make pretty things. By which they mean: the classically beautiful, the academically sanctioned—artistic nudes, painterly landscapes, tasteful portraits. These questions come from the same individuals who gladly consume horror and sci fi films. The monster, it seems, is allowed to roam the theater, but not the gallery.

The Divine Monstrous Feminine

“Verily at the first Chaos came to be, but next wide-bosomed Earth, the ever-sure foundation of all the deathless ones…”

—Hesiod, Theogony

Having successfully caged the monster, let us turn now to the generative, maternal aspect of monstrosity. My second creature is affectionately named (or, rather, unnamed) “Lizard.” She comes from an all-female brood of parthenogenetic lizard nuns—identical genetic clones of a singular proto-lizard mother, whom they worship as divine. With her, I wanted to pay homage to Jim Henson’s puppetry, especially The Dark Crystal, hence the puppet beak, which I also think works well to suggest a gummy, toothless old woman—a lizard. To emphasize their virginal and devotional nature as parthenogenetic clones, I dressed her in a draping robe and babushka hood modeled after Renaissance depictions of the Virgin Mary. For her form, I drew inspiration from geese, turkeys, lizards, and toucans—animals cruelly invoked in caricatures of aging women (the spinster as goose, the crone as lizard).

I am particularly proud of her beak, which proved technically challenging for two reasons: First, sculpting the illusion of a rigid, hard-palated beak beneath the loose, sagging folds of skin while balancing anatomical credibility with puppet logic. And second, resolving the complex edge flow at the corner of the mouth, where the upper lip, lower lip, and the hinged “puppet seam” converge. The subtle dimple that formed there is beautiful.

So much theory has been written about monsters and the monstrous. Normally, the critical approach to the monster is to examine its myth in sociocultural context, to extract (rather predictably) the real human fears and anxieties that made the myth. Countless books promise insights into ‘what monsters tell us about ourselves,’ only to inevitably arrive at the tired revelation that humanity is the ultimate monster wah wah wah. Likewise, contemporary horror cinema overwhelmingly insists that generational trauma is the ultimate bogeyman stalking mankind. But there is monstrosity in motherhood. Marie-Hélène Huet, in Introduction to Monstrous Imagination, recounts how, for centuries, the mother’s imagination was believed to shape the fetus—and was often blamed for monstrous birth. A pregnant woman who looked too long at a statue, or gave in to errant desires, might mark her child with animal features or deformities. The monster was the phenotypic hallucination of maternal whim, desire, or sin.

Motherhood is necessarily abject, parasitic, not unlike the artistic act. Huet writes:

"The theory that confers on the maternal imagination the power to shape progeny also suggests a complex relationship between procreation and art, for imagination is moved by passion and works in a mimetic way.”

If ordinary procreation is a collaboration between paternal and maternal forces, monstrous birth, in the patriarchal imagination Huet describes, is the result of the mother’s unchecked auteurship. When the natural order is violated, the womb (and woman) becomes a portal to the void, l’informe, from which the monster is born and made real. This is the threat of the monstrous womb, as theorized by Barbara Creed and depicted in films like Cronenberg’s The Brood. The association between parthenogenesis and the monstrous spans many cosmologies of old: Gaia birthed the Titans; Tiamat spawned dragons, serpents, and demons; Ymir sweated out a race of giants from his armpits and legs; Even today, the monstrous womb continues to fascinate; The Observer dubbed 2024 “The Year of the Demon Baby” in cinema, as four films released last year featured scenes with monstrous births (Alien: Romulus, Immaculate, The First Omen, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice).

Monstrous birth is more uncanny than scary, however. The divine also has always been depicted through impossible births: virgin mothers, world-eggs, gods emerging from sea foam or splitting from foreheads. In designing my creatures, I try to channel the divine monstrous maternity Huet posits, where imagination births reality ex nihilo, my Wacom tablet a sacred womb. Strangely enough, I can’t help but feel a maternal attachment to them either. There is truth that no one will ever love you like your mother, just as there is a strange reflex to empathize with someone when you see their baby photos, because it means knowing them in a state of innocence. And, in both cases, it is to see yourself in them.

Historically, poltergeists and other psychokinetic phenomena have been interpreted as manifestations of adolescent psychic unrest, symptoms of repressed emotions erupting outward. In the same way, the psychic progeny of the monstrous womb often act out the unconscious desires of their mother. In The Brood, Nora Carveth’s psychoparthenogenetic spawn murder her abusive mother, enacting her repressed rage through an act of matricide committed on her behalf. This is disturbing, because it inverts the matryoshka from an engine of recursion—birthing within birthing—into an ouroboric cycle of consumption: matriphagy, where each monstrous birth devours its mother. Art, likewise, is never simply the child of intention, but the monster that inherits the submerged desires of its creator. Perhaps Picasso knew this when he rendered his own visage, especially the eyes, on the faces of his figures. Every monster is an obsidian mirror, every act of creation a moment of self-disclosure, whether we intend it or not.

Eschatology of Entropy

“You cannot see My face, for no one can see Me and live.”

Exodus 33:20

While the maternal monster may birth reality out of the void, the artistic process often feels more like coaxing forms out of formless static. My third creature is actually a pair—jockey and steed—born from a self-imposed work-in-progress challenge to design a sentient rider and his bestial mount endemic to the same biosphere. When selling the illusion that two creatures evolved along the same phylogenetic branch, consistency of form is key. Shared anatomical features become visual leitmotifs, vestigial forms nightfished from the same depths of a churning black ocean of abstraction. The most telling of these forms are signs of symbiotic coevolution; like the natural saddle that time carved between horse and rider, the jockey’s steed bears a riding horn formed by shoulder girdle. Both creatures exhibit the muscular signature of their bond in their strong quadriceps and backs, but their postures and carriages clearly distinguish rider from mount.

The divergence in cognitive capacity manifests first in orbital placement: where evolutionary pressure has drawn the jockey's eyes forward into predatory convergence, his steed's laterally-positioned orbitals remain fixed in the perpetual vigilance of prey (though its hammerhead profile and stocky build still suggest a certain brutality). Their craniums tell a similar story of divergent intelligence. While both skulls suggest an underlying hemispheric brain, the jockey's compact cranium bulges prominently, whereas the steed's flattened skull dedicates most of its frontal architecture to supporting those wide-set orbital structures. The sensory organs of the jockey are also altogether more developed. Though both creatures share a similar star-nosed olfactory structure, the jockey's has evolved into an elegant organ with delicate sensory fronds radiating from a centralized olfactory bulb, while the steed's remains broad and crude, as if hewn from stone rather than sculpted by selective pressure. The jockey’s organ also rests above a markedly human nasal cavity, from which nasolabial folds transition into narrow gastropodic mouthflaps. The steed, by contrast, has a wide maw and gluttonous, sagging gullet that emblematizes its basedness.

As I have implied, these forms do not come from nowhere, but from a sea of shape information, a mental library stocked by continuous observation and appreciation of form. I repeat myself, Inspiration comes from everywhere—like the noble star-nosed mole, whose eyes are weak, but whose solar nose illuminates the subterranean dark. What other shapes have I stolen? Well, the jockey's conical skull recalls the mantle of a squid, his mouth the tentacular o-ring of a mussel's mantle edge, and his cheek lobes the leather flaps of an aviator or jockey’s cap, to name a few. I have always been struck by the design of the xenomorph, Giger’s biomechanical scorpion: for its snaking clavicle that coils around to the vertebral vents of its spine; its chronically foggy, phallic visor that cradles a hollow human skull. The xenomorph is symbiotic too—it takes the traits of its host. But its design suggests borrowing of more than just human DNA. It evolved the forms of a spacesuit… Just brilliant. I might as well be the xenomorph, because I stole the very same clavicular form for the shoulder girdle of the steed, a rigid tubular ring ready for airlock.

Beyond its scorpion-like qualities, the xenomorph's lustrous black exoskeleton evokes the rhinoceros beetle's armored carapace and crowning warhorns. In designing the steed, I wanted to capture the rhinoceros beetle’s regality, the way royal mounts throughout history have served not merely as transportation but as declarations: to the ruler, the domestication of wild beasts like elephants and horses symbolizes their dominion over wild natural forces, in addition to their subjects. The stocky, compact body of the beetle suggests coiled potential, like a compressed spring holding tremendous force in reserve or a generous king tempering his might. This quality is found in many renderings of wild animals in art, like the encircling lions in Peter Paul Rubens' Daniel in the Lion's Den, where the composition implies no escape except upwards, to God, from the beasts of nature—some sleeping and indifferent, others poised with the arching gestural lines of predators about to strike. Or like the Imperial Chinese guardian lions or Foo Dogs, who boast exaggerated human musculature and domineeringly grip an earth-like ball under paw.

Sage artistic wisdom says to take forms from nature, and for good reason: God is the master architect of form. Others have noted this too, like John Keel and F. W. Holiday, who in their books The Eighth Tower and The Goblin Universe, both advance similar hypotheses that our universe is stranger than we understand, that there exist higher planes of existence from which astral travelers, cryptids, aliens, faeries, spirits, angels, demons, all visit us. Notably, the discourse around UFOs has shifted in recent years: UFO (Unidentified Flying Object) has been rebranded to UAP (Unidentified Aerial Phenomena) to suggest entities might travel via means other than flight or that they might not be material objects at all, and ET (extraterrestrial) to NHI (Non-human Intelligence) to imply an origin beyond outer space, perhaps even an extradimensional one. Of God and form, Keel and Holiday both write:

But today it is apparent that the same force that answers some prayers also causes it to rain anchovies and is behind everything from sea serpents to flying saucers. It distorts our reality whimsically, perhaps out of boredom, or perhaps because it is a little crazy […] If God, the Cosmic Mind, alone is responsible for all of the absurd life forms here, we have another good reason to question His sanity.

The Eighth Tower: On Ultraterrestrials and the Superspectrum by John Keel

It enjoys the grotesque and even the horrifying. It is both spendthrift and immensely economical. It labors to perfect the seemingly impossible just for fun. Above all, it has an awareness of beauty in form and structure that dazzles the mind.

The Goblin Universe by F. W. Holiday

Shallow understandings of God might associate His creation with only the classically beautiful, the explicitly symmetrical, linear, and golden-ratioed, but, as Holiday observes, God is also partial to the beautifully grotesque. We live on the same planet as funguses which invade the brains of insects and zombify them, vampire bats that subsist entirely on blood and share meals through regurgitation, and parasitic wasps that inject their eggs into living caterpillars, whose larvae then devour their hosts from the inside out while keeping them alive until the final moment. These organisms are cartoonishly monstrous, and some might use their existence as evidence of the indifference of the universe, the nonexistence of an intelligent Creator. But to me they prove the opposite: Their beauty lies in biological processes so far removed from human experience that they seem like alien technologies; the cordyceps fungus hijacks neural pathways with surgical precision, while the wasp possesses an uncanny ability to keep its host in a state of living suspended animation. These are not simple predator-prey relationships but intricate biochemical symphonies that operate according to logics we can barely comprehend. They are so complexly ordered so as to at first seem disordered, and this is the Divine.

If God is omnipotent, He is infinite potential, which means He embodies the potential for all possibilities, including the grotesque and horrifying. To us, with our narrow human minds, God too would seem entropic, despite being highly ordered and perfect; this is what it means to be ineffable. Many might prefer saccharine, straightforward, predictable, palatable popular music to chaotic, cacophonous, dissonant, discordant noise music, but behind the noise is a complex underlying logic just the same. The architect's darling brutalism and its harsh concrete forms can alienate the casual observer, who might prefer the familiar harmony of neoclassical style. The bitter bite of fermentation is harder to appreciate in food than ultra-processed slop engineered for flavor and mass appeal. As we approach the complex, we are challenged to expand our capacity for appreciation of form, to try and glimpse the Divine, to achieve aesthetic theosis through an ever-oscillating ostranenie. Art attempts to make the ineffable effable, to bring something from nothing (noise) into being (sense). And what more directly captures the essence of creating something utterly alien but familiar than creating a monster?

When I describe my process as coaxing forms from chaos, I do not mean it metaphorically. There is a technique in 3D called kitbashing—a term borrowed from model-making, where loose plastic components are salvaged from various kits and recombined into something new. In digital sculpting, this means pushing abstract shapes together, morphing and melding them until the pareidolic center of the brain hallucinates interesting forms in the noise, a bit like finding zoo animals in clouds. Curiously, the mind sees in the noise what it has been trained to see: mecha artists see robots; vehicle artists see cars; I see monsters. Once content with the emergent forms, it is the artists’ job to polish them by pushing, merging, or discarding. Below is a timelapse of the kitbashing process for the jockey using a technique I learned from Pablo Munoz Gomez’s Original Creature Concepts course:

At this point, I will also begin to theorize a myth to animate the creature. This process is iterative and recursive: whereas initially the abstract forms inform the myth, the myth now drives the direction that I polish the forms. For the jockey, his carapace head and mole snout, coupled with my current interest in eschatology, the study of the end of the world, led me to imagine him as a subterranean fifth horseman of the apocalypse, which begged the question of what he might represent…Conquest, War, Famine, Pestilence…Entropy? This back-and-forth between form and meaning mirrors something fundamental about how complexity arises. Essentially all creation is emergent; this is especially true of intelligence. All around us, low-level biochemical rules generate eerie, hyper-intelligent outcomes. The most alien lifeforms are emergent collective intelligences like economy, neural networks, the internet, the state. These entities exhibit behaviors and patterns that transcend the understanding of their constituent parts—us. They are more than the sum of their human components, yet they remain fundamentally incomprehensible to the very minds that birthed them. If we cannot fathom these emergent intelligences, which are merely higher-order expressions of ourselves, how can we ever expect to fathom the Divine?

In Gödel, Escher, Bach, Douglas Hofstadter argued that recursion is fundamental to human consciousness, but paradoxically, most people struggle to grasp it explicitly. The recursive entanglement of form and myth isn’t confined to the studio. It operates even more powerfully in the wild: once a monster is released into culture, it continues to evolve, acquiring new meanings and shapes as it is retold, reinterpreted, and reimagined. Each iteration is both a reflection of collective imagination and a force that pushes the myth in new directions. Once unleashed, the monster accumulates its own memetic history and generates new cycles of form and meaning. Perhaps to illustrate we can reformulate our fundamental equation Monster = Creature + Myth to account for the interplay between Creature and Myth in a more recursive, generative, parthenogenetic series:

where:

Instead of being shaped by biological pressures, the monster is shaped by memetic pressures, beginning as an abstraction and scaling in complexity, like an asteroid collecting debris in its orbit until it gains its own gravitational field, pulling in ever-larger fragments that in turn reshape both the core and its expanding sphere of influence. Hofstadter is right—this dynamic mutation is difficult to model because it operates like the collective intelligences mentioned previously: recursive, unpredictable, and emergent. More broadly, any idea behaves the same way; like a memetic monster, it mutates and hybridizes across generations, shaped by collective imagination and cultural feedback. Monsters merely dramatize this process, embodying the very logic of memetic evolution that underlies creativity itself by showing us, in the grotesque and the hybrid, how novelty and complexity emerge from the churn of culture like traces on a palimpsest. Monsters show us their viscera.

Of course, while the larger evolution of ideas is wild and recursive, the process of shaping a single piece of art calls for order: a way to make complexity legible, both to the artist and to their audience. In the Western music tradition, a song begins with abstract chords, elaborated into melody by notes; literature begins with the broad shape of a story, resolved by chapter, sentence, and word; drawing begins with composition and gesture, developed through line, shape, value, and ultimately refined into detail; food starts with a flavor profile, brought to life through choice of ingredients and techniques. Each level of the hierarchy of detail works to serve every other level and by extension, the whole, still through self reference, nested abstraction, and fractal logic, but in a systematic, linearized process. No wonder the sculptor is instructed to sculpt in primary, secondary, and tertiary forms. It makes elegant complexity possible by reducing cognitive load. Ours is a human solution, bounded by cognition, to the monstrous generative logic that animates nature at a scale only God could comprehend.

Myth itself has acknowledged this truth. Hermetic tradition incants “As above, so below” to imply a metaphysical symmetry between Heaven and Earth, between God’s creative logic and our own. Further, it reflects the same recursive logic of patterns echoing across scales. Trunk gives way to branches give way to twigs give way to leaves give way to veins give way to cells give way to organelles give way to molecules give way to atoms and so on… Or, there is the mytheme of the World Turtle, a great turtle upon which the entire universe rests, and which has been used to illustrate the concept of infinite regress, by suggesting that the turtle rests atop another turtle atop another turtle atop another turtle atop another turtle…Maybe it really is turtles all the way down.

The Gatekeepers

“The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.”

—Antonio Gramsci

There is a nasty strain of anti-intellectualism infecting the American public, many of whom are stuck on the old academic lie that only traditional art, the kind they think requires “skill” (read: realistic rendering), is real art, when, in reality, many of their favorites—Monet, Degas, Klimt, Rockwell, Hopper—are not realist at all. It is probably the MoMA curator’s bane to hear the millionth visitor remark, “I could make that,” upon standing beneath their first Rothko. Most people erroneously disparage “modern art,” not realizing that what they actually mean is “contemporary art,” for being “too pretentious.” If they are feeling extra daring, they might smugly add that “art is just tax evasion for the ultrawealthy.” These criticisms emerge perhaps because the art world has, in many ways, abandoned the public and obscured the appreciation of art by all but retiring the Western art history narrative, the creation myth of its own making. Oh, how every generation must remark, “Art is dead.”

But when the public rejects contemporary art for being “pretentious,” they are doing so based on ideological, rather than aesthetic, criteria. I will appropriate the term ArtPower (after Foucault’s BioPower) from Boris Groys’ book of the same name to describe this phenomenon—a term Groys develops primarily in the context of totalitarian art and propaganda, though he also gestures toward its relevance for Western art, in that Western art today is as he says “exhibited for the masses at international exhibitions, biennials, and festivals.” The exercise of ArtPower is a very real, and, I will cautiously add, historically fascist tradition: Famously, the Nazis harbored similar harsh feelings towards what they also called “modern art,” by which they meant art with Jewish, Communist, or Freemasonic influence, deeming it “degenerate.” Stalin installed the state-sponsored Soviet Realism movement as the official and only artistic movement permissible under the Soviet Union, suppressing avant-garde movements like Constructivism. And so, the American public's resistance to contemporary art is more a rejection of institutional gatekeeping and performative intellectualism that makes them feel excluded or diminished in the social order than any specific aesthetic judgment.

If we consider our earlier argument, the power that controls what is considered art is actually policing the definition of divinity. Largely, ArtPower is wielded by Academe through fields of critical theory like "postanthropocentrism," "queer studies," "postcolonialism," etc. This is the bleeding edge of radical thought that informs contemporary art, theory that promises to shatter conventional boundaries and reimagine what art can be. Yet most theory offers only a vague way forward in terms of praxis. Theory without praxis is like myth without creature, and, despite all this theoretical sophistication, when we examine the creature that emerges to accompany Academe's myth, we arrive at...more zombie figuration. The same human forms, though now specifically of marginalized 'queer, black, brown, or female bodies.'

It is not that these subjects are unworthy (I am certainly for representation), but that they have been ossified into new orthodoxies of their own. They’ve become untouchable, ritualized, or policed in their own right, and radical they are not... These exhibitions will probably be accompanied by an artist or curator’s statement along the lines of “In a society bleeding with systematic injustice, the most radically defiant act is to simply exist as a black or brown person…" Round of applause, everyone. Figurative painter #123456 solved racism. I admire the work of Kehinde Wiley, Kerry James Marshall, Simone Leigh because they were their own—but must every young black or brown artist now make the same thing? As a Mexican-American myself (race card, I know), exhibits like these make my hairs stand on edge. Like, “Ok, you can sit at the cool kid’s table, but only if you let us remind you of your Otherness. And your body? We own that too.” Institutions use marginalized “bodies” as human shield to claim sacrosanctity—concealing the poverty of their ideas and their impotence to bring about the utopia they endlessly theorize by using the artist’s Otherness as a convenient stand-in for radical thought. And the artist? They are rewarded with institutional validation, to the neglect of creative risk and dignity. Mutual symbiosis. The call is coming from inside the house. We are the monster. Meanwhile, the public, and especially marginalized groups with little access to or interest in higher academic frameworks, don’t even know what critical theory is (nor, probably, that they are reading it now, lol); hence the moral panic surrounding supposedly radical “critical race theory,” which none of its detractors could even define, much less had read. This speaks to the pure performativity of it all, the pure ideology (to be read in Žižek’s voice). Academe is no less alien than the Greys who abducted Betty and Barney Hill — mutilating sacred cows, dissecting black bodies, and speaking in tongues.

This class dimension reveals the deeper mechanics of aesthetic warfare. It is a religious crusade, each side vying for the divinity of their gods. Each group genuinely believe their aesthetic values are sacred/transcendent, not just matters of taste— ArtPower. The public's attachment to "traditional" art is the aesthetic expression of a petit bourgeois anxiety about cultural legitimacy. Working-class communities often embrace representational art because it signals accessibility and shared cultural values, while the middle class clings to Renaissance ideals as markers of respectability and education. Meanwhile, the upper middle class academic establishment weaponizes theoretical complexity as cultural capital, creating deliberately obscure frameworks that exclude those without advanced degrees or wealth. Or, to extend the metaphor, the public worships the elder gods of representation, Renaissance, and classical traditionalist painting, while Academe promises salvation through new false gods.

Within every religion there is also taboo, and within every culture there is also permissible transgression. Bataille wrote favorably of the Roman saturnalia, a festival of reversals where, for a day, slave became master and jester became priest, a subversion of the social order which he argued was fundamental to society:

The necessity for reversal is so important that it had, at one time, its consecration: there is no constitution of society which does not have, on the other hand, the challenging of its foundations; rituals show it: the saturnalias or festivals of madmen reversed the roles. [And the profundity from whence descended blindly the feeling which determined the rituals—the numerous, intimate links between the themes of the carnival and the putting to death of kings indicate this sufficiently enough.]

Inner Experience by Georges Bataille

While for Bataille, the excitement of saturnalia lay in the dissolution of boundaries between the sacred and the profane and in the excessive expenditure of surplus, his contemporary Mikhail Bakhtin understood carnival more as a sanctioned “safety-valve,” a controlled release of social tension that ultimately reinforced the stability of hierarchical structures. One might consider the modern bachelor party in this light: a temporary suspension of moral norms, permitting infidelity and debauchery as symbolic transgression, only to reaffirm the social contract of marriage. Even events like the Capitol insurrection of January 6th, a failed coup against political order, unfolded as a ritualized public spectacle through which the state was able to reassert its legitimacy and sovereignty. Anthropologists have studied such reversals extensively, especially in connection to tribal coming-of-age ritual, like the Aboriginal bush walk or Maori shark hunt:

“The novices are, in fact, temporarily undefined, beyond the normative social structure. This weakens them, since they have no rights over others. But it also liberates them from structural obligations. It places them too in a close connection with non-social or asocial powers of life and death. Hence the frequent comparison of novices with, on the one hand, ghosts, gods, or ancestors, and, on the other, with animals or birds … In liminality … former rights and obligations are suspended, the social order may seem to have been turned upside down, but by way of compensation cosmological systems (as objects of serious study) may become of central importance for the novices. […] The factors or elements of culture may be recombined in numerous, often grotesque ways, grotesque because they are arrayed in terms of possible or fantasied rather than experienced combinations—thus a monster disguise may combine human, animal, and vegetable features in an ‘unnatural’ way, while the same features may be differently, but equally ‘unnaturally’ combined in a painting or described in a tale. In other words, in liminality people ‘play’ with the elements of the familiar and defamiliarize them. Novelty emerges from unprecedented combinations of familiar objects.”

—Victor Turner, quoted in George P. Hansen, The Trickster and the Paranormal

These rituals paradoxically exist as allowable subversions of social order within the social order itself. They are forms of controlled rebellion, a ludic cathartic framework for adolescents to safely transgress as they come of age without truly threatening the established order. Most artistic transgression is similarly safely performative. That is the orthodoxy of academe: choreographed rebellion masquerades as revolution, transgressions picked from preselected categories serving the very systems they claim to subvert. The contemporary art world has perfected the art of toothless provocation: shocking enough to generate press coverage and grant applications, tame enough to hang in corporate lobbies. The true radical theory is theory that academe will not permit, that which is not respected: fringe science like UFOlogy, cryptozoology, parapsychology, conspiracy theory, the occult, and all manner of knowledge practices dismissed as pseudoscience or delusion. Academics are only allowed to study such practice if they acknowledge it as myth or folklore, something to be interpreted psychoanalytically, something from which to extract metaphor and moral or help define “new modalities of thought,” but not to faithfully believe. What academe really fears is authentic, unperformative transgression that they cannot categorize or control, the cognitohazardous monster that refuses to be caged. True radicalism begins where academic respectability ends: in the wilderness, beyond the pale, under the ground, in the night, from utter silence…

I say all this not as a reactionary, but as a discontent reader and appreciator of art who now struggles to find anything good to read or appreciate. Where did all the good art go? When were all the monsters caged? Of course, I know this is itself a cliché complaint of our time, repeated so often it has become its own ritual of disappointment. And the still faithful receive the same tired answers to their prayers, too: “Not in academia, that’s for sure!” “Try reading zines, blogs, or forums. That’s where the truly radical is today!” “I’m in a niche private Discord of xenofeminist solarpunk acephalic cybernetic DIY transhuman biohacktivists. It’s sooo radical, but sorry, link is dead.” Or, “Try aaaaarg.fail or monoskop or this private tracker that will take you ten years to join, just to be shadowbanned by a random Russian for connecting to their IPFS with a VPN, but not before downloading a few bitcoin miners.” Perhaps the real answer is that what I am looking for, what many are looking for, is not to be found in what can be easily named, classified, or found in any forum or canon. The Divine, after all, emerges most clearly through the grotesque, the monstrous, the violation of all categories. Apophatic theology (or negative theology) seeks to know the Divine by way of negation: by saying only what cannot be said about God. The Divine is most present when all other categories fail. We must wonder: is this epistemic limitation actually divine prohibition at work, the forbidden fruit keeping us from Eden’s gates? If the Divine can only be approached through absence, perhaps the same logic governs the creative act. The monsters we cannot make, the forms that remain forbidden, quietly map the boundaries of whatever gods we serve—academic institution; culture and taboo; the state; the Most High God Himself.

If I were more inclined toward schizoconspiratorial thinking, I might suspect there really is a grand shadow-governmental conspiracy against making truly good, radical art. (Dangerous thought—freethinker detected.) In such moments of mania, I’m tempted to invoke a familiar paranoiac adage, widely misattributed to Voltaire, about power and what cannot be criticized. The actual source is a white nationalist propagandist, which should give us pause about both its origin and its reasoning. Yet the persistent spread of this idea in spite of its questionable provenance only illustrates another truth of power and prohibition: the idea persists precisely because it is prohibited. Some monsters deserve to stay caged. To create some much-needed critical distance, I paraphrase:

If you want to know who your masters are, ask yourself who you can’t criticize.

And, if I might reframe:

If you want to know who your God is, ask yourself what you can’t create.